SPIRITUALITY IN NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE

One of the most commonly dissected themes that authors of every descent, heritage, and culture choose to explore in their writing is the theme of spirituality. As with the weighty and difficult themes of ethnocentrism, racism, and morality, the theme of spirituality provides the Native American author with the unique opportunity to enlighten the reader and foster a feeling of understanding through interiority that speaks to the human experience, either facet by facet or as a whole. Authors Paula Gunn Allen, Louise Erdrich, Linda Hogan, and Tim Tingle in their respective works "Deer Woman," "The Fat Man's Race," "Aunt Moon's Young Man," and "The Beating of Wings" delve into the multifaceted theme of spirituality in Native American culture through taut narrative structure, supernatural phenomena, shifts in diction and syntax, and powerful protagonists.

"Deer Woman"

by

Tone Aanderaa

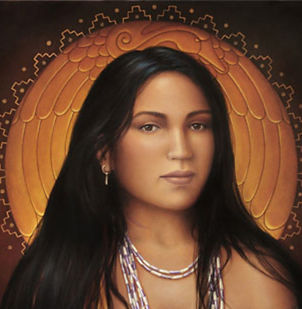

This painting of the Native American spiritual figure, Deer Woman, encompasses Allen's reverence of the theme of spirituality in her work, as well as the darkness, cunning, and power of the Deer Woman inherent in the story.

"DEER WOMAN" BY PAULA GUNN ALLEN

Paula Gunn Allen addresses the theme of Native American spirituality in her short story, "Deer Woman." Allen employs supernatural elements, strong characters, an unbiased narrator, and a linear chronological narrative structure to tackle this important theme in Native American literature. Allen slowly shifts the reader into focusing on the theme of spirituality by showing a shift in the protagonists, Ray and Jackie, and their perception of reality on page 61: "She held his eyes with hers. 'Where are you parked?' They made their way to the pickup and got in. It was a tight fit, but nobody seemed to mind. Ray drove, backing the pickup carefully to thread among the haphazardly parked vehicles that had surrounded theirs while they were at the dance. As he did, he glanced down for a second, and thought he saw the feet of both women as deer hooves" (Allen 61). Allen adeptly layers in elements of the Deer Woman tale as the men perceive them in the story, as in the above passage. This facet of her work is not only helpful to the protagonists as they discover stranger and stranger elements of the Deer Woman story, but it is also helpful to readers who are ignorant of the folk lore.

Allen continues building up the theme of spirituality in the piece as the story progresses, and the reader is keen to this fact through Allen's shift in language throughout the story. An excellent instance of this fact occurs on page 62, after the men have followed Junella and Linda through a creekbed to get to a fantastic party: "A moment later the women appeared. Their long, flowing hair was gone, and their heads shone in the soft light that filled the area, allowing distant features to recede into its haze. The women wore soft clothing that completely covered their bodies, event their hands and feet. It seemed to be of a bright, gleaming cloth that reflected the light at the same intensity as their bald heads. Their dark eyes seemed huge and luminous against skin that somehow gave off a soft radiance. Seeing them, both men were nearly overcome with fear. They have no hair at all, Ray thought. Where is this place?" (Allen 62-3). Earlier in the piece, Allen focused on buildling the complex characters of Ray and Jackie to further the rapport and intimacy with the reader. In doing so, she also accomplishes the feat of easing the reader into an alternate reality that is consistent with the spiritual lore of the Deer Woman (or in this case, women) so that it is equally shocking and fascinating.

Finally, Allen shares her perspective on Native American spirituality in the final pages of the story, which is a perspective of reverence and respect for the indigenous peoples' spiritual practices. Allen takes care to convey the Deer Woman (Women) in a beautiful, attractive way, conveying them nearly as goddesses through the eyes of Ray and Jackie in the story. What is most incredible to expereince is the ending of the piece, which underscores Allen's respect of the Native American spirituality she addresses in "Deer Woman:" "'But you know,' Ray said, 'the weird thing is that he'd evidently been telling someone all about that time inside the mountain, and that he'd married her, and about some other stuff, stuff I guess he wasn't supposed to tell.' Another guy down on his luck, he guessed. 'Remember how I was telling you about my crazy uncle, the one who used to tell about Deer Woman? Until I heard about Jackie, I'd forgotten that the old man used to say that the ones who stayed there were never supposed to talk about it. If they did, they died in short order'" (Allen 64). Allen manages to conclude the story in the same mysterious and unsettling fashion that the Deer Woman left both Jackie and Ray in the story, which hearkens back to her ability to ease in and out of the spiritual elements of the work.

"Native American Beauty"

by

CAM Jr.

This photograph of the Tlingit and Koyukon-Athabascan actor and director Martin Sensmeier showcases powerful seductive qualities found in the devil character in Erdrich's "The Fat Man's Race."

"THE FAT MAN'S RACE" BY LOUISE ERDRICH

Erdrich, like Allen in "Deer Woman," tackles the weighty and important theme of Native American spirituality and its consequences in her short story, "The Fat Man's Race." Erdrich leverages the theme against a foundation of humor, casual language that hearkens back to the Native American tradition of oral story telling, a close psychological distance between the narrator and the reader, and narrative structure that is bookended by a realistic introduction and conclusion. Erdrich's decision to employ these specific literary elements leads the reader to better understand her position on spirituality throughout the piece. While Allen gently eases the reader, who may or may not be aware of the folklore of the Deer Woman, into her story, Erdrich uses a blunt, concise, and arrow-head-sharp approach: "I was going to marry Cuthbert and had the date of the wedding all picked out, but then his sisters turned him against me. They told him I was after his money, I wanted his land, and also that I was having sex with the devil. Only that last part was true" (Erdrich 65). Erdrich's approach provides the reader with the total-immersion experience of this concept of Native American spirituality, thus allowing him or her to follow Erdich's sharp narrative more easily.

Like Allen, Erdrich uses believable supernatural phenomena to convey the human qualities of the spiritual beings she describes in her work: "I was visited at night in my dreams by a man in blue --a blue suit, a blue shirt, a blue tie, blue shoes, but no hat. He had black hair and black eyes, skin the color of a pale, brown egg, very smooth and markless. He would take off all his blue clothes and lay them at my feet. His instrument of pleasure --don't laugh at me -- was blue also, as though dipped in beautiful ink, midnight at the tip. I would admire him, then I would lie with him all night...He said the sweetest things to me, like a good angel, but the things he did were darkly inspired" (Erdrich 65). Erdrich strikes a keen balance between the spiritual lore and the narrator's real-life expectations in the story, weaving in the threads of lore carefully to expose her perspective on the theme of Native American spirituality through her protagonist.

By creating a protagonist who chooses to tackle her demons head on, both literally and figuratively, Erdrich creates a dichotomy in her perspectives on Native American spirituality; one one hand, "The Fat Man's Race" implies that she reveres spirituality enough to discuss its serious and mortal consequences, but on the other hand, her mocking tone, casual, colloquial language, and choice to create a real-life framework for the spiritual elements all underscore her ability to also view the Native American spirituality through a humorous, almost satirical lens. Erdrich's ability to deftly handle the subject of spirituality in her piece speaks to her literary talent and perspective on Native American spirituality in "The Fat Man's Race."

Untitled

This painting of a Native American woman encompasses the empathy, mystery, wisdom, identity, strength, and pride in her knowledge and heritage that Aunt Moon has in Linda Hogan's "Aunt Moon." The painting additionally has an ethereal quality that hearkens back to Hogan's subtle discussion of spirituality in her work.

"AUNT MOON'S YOUNG MAN" BY LINDA HOGAN

Linda Hogan's short story entitled "Aunt Moon's Young Man" tackles the theme of spirituality through the complex characters of Bess Evening, Isaac Cade, and the protagonist and narrator. Unlike Allen and Erdrich in their stories, Hogan employs the critical tool of subtlety and uses the general concept of spirituality to speak to a variety of Native American peoples, traditions, and belief systems. Hogan's literary nuance and ability to address the theme of spirituality in a wide variety of peoples is built on the foundation of psychological intimacy with the innocent protagonist early in the story: "Bess pretended to be looking at the little Jersey cattle in the distance, but I could tell she was seeing that man...I didn't know if it was just me or if his presence charged the air, but suddenly the oxygen was gone. It was like the fire at the Fischer hardware when all the air was drawn into the flame. Even the chickens clucked softly, as if suffocating, and the cattle were more silent in the straw. The pulse in everything changed. I don't know what would have happened if the rooster hadn't crowed just then, but he did, ad everything returned to normal" (Hogan 68-9). Immediately, the reader understands that the narrator is unbiased, that Bess is a character whose differences from the other characters draw the reader to her, and that the man (Isaac) has a unique power over the people he encounters, all of which set up the story to deal with the theme of spirituality.

A facet of Native American spirituality that Hogan directly addresses and shows reverence to in her poetic diction and syntax occurs on page 71 of the story: "This is how I came to ca Bessie Evening by the name of Aunt Moon: She'd been teaching me that animals and all life should be greeted properly as our kinfolk. 'Good day, Uncle,' I learned to say to the longhorn as I passed by on the road. 'Good morning, cousins. Is there something you need?' I'd say to the sparrows. And one night when the moon was passing over Bessie's house, I said 'Hello, Aunt Moon. I see you are full of silver again tonight'" (Hogan 71). Hogan confronts the Native American spiritual value of respect for all things living in the aformentioned passage, ergo furthering her piece's appeal to pan-Native American tribes and furthering her authorial perspective on Native American spirituality. Hogan continues this idea of interconnectedness between all forms of life in the narrator's character: "Sometimes, when I was with her, I knew the older Indian world was still here and I'd feel it in my skin and hear the night sounds speak to me, hear the voice of water tell stories about people who lived here before, and the deep songs came out from the hills" (Hogan 71).

Finally, Hogan gives a sense of physicality to the concept of spirituality as Allen and Erdrich do in their respective stories, "Deer Woman" and "The Fat Man's Race," but again, in her own subtle way. Hogan weaves the idea of the soul of a person being a young man or woman inside his or her eye throughout the story. Hogan utilizes this aspect of spirituality in "Aunt Moon's Young Man" to give weight to the theme, as well as a sense of loss, sadness, or joy in the story. Two excellent examples of this idea occur on pages 73 and 74: "Shortly after the fair, we heard that the young man inside Aunt Moon's eye was gone. A week passed and he didn't return... Aunt Moon's hair was down. Her hands were on her lap," and "All the next morning, driving through the deep blue sky, I thought how all the women had gold teeth and hearts like withered raisins. I hoped Jim Tens would marry one of the Tubby girls. I didn't know if I'd ever go home or not. I had Aunt Moon's herbs in my bag, and the eagle feather wrapped safe in a scarf. And I had a small, beautiful woman in my eye" (Hogan 73-4). Hogan's grasp of the general sense of the soul and the shared human experiences of utter happiness and astounding pain serve as the tools she uses to deal with the theme of Native American spirituality in "Aunt Moon's Young Man."

"The Owl's Telling"

by

Blackbear Bosin

This piece of art showcases the terror, strength, and power of the Owl Man in Tingle's "The Beating of Wings."

"THE BEATING OF WINGS" BY TIM TINGLE

Perhaps the strongest and soundest example of the theme of Native American spirituality in among this collection of stories is Tim Tingle's "The Beating of Wings." Tingle is on the opposite end of the spectrum from Hogan in her story "Aunt Moon's Young Man." Tingle builds his story on the blatant belief in Choctaw spirituality and the stark examples therein, such as in the introduction of the piece: "Jimmy's heart pounded like a wounded rabbit's. His breath came in hard short gasps...The owl was sitting on a stump, gently lifting and lowering his wings. As Jimmy Ben watched with eyes as big as the moon, the owl flapped his wings and hovered three feet above the tree stump. He seemed to float there for several minutes, then he stepped on the stump with the legs of a man. It was the body of an owl and the legs of a man" (Tingle 78). Tingle avoids subtlety in his piece to further the gravity of the situation Jimmy Ben experiences, which draws the reader closer in empathy to him to better understand his perspective, as Allen, Hogan, and Erdrich do in their stories.

Also, like Hogan, Allen, and Erdrich, Tingle's piece uses the foundation of tradition and pride in one's Native American heritage to further expound on the theme of spirituality, as highlighted in the rabbit hunting scene with Jimmy and his grandfather: "He removed a handful of feathered darts from his saddlebag. One end of each was tipped with a sharp thorn. 'Your blow gun can protect you, Jimmy, if you learn to use it. A man-owl is after you. That's serious business. Don't think he's not coming back. He is. He will never leave you alone, not as long as he is alive" ( Tingle 81). Tingle's authorial decision to accept the spiritual phenomena as authentic and real causes the reader to accept the spiritual phenomena as authentic and real, too. This simple decision on his part heightens his credibility and empathy as an author as well as his appeal to a variety of Native American and even non-Native peoples.

A unique aspect of Tingle's "The Beating of Wings" is his ability to use the Choctaw spirituality to appeal to a broader group of people, as opposed to using the broader concept of spirituality and religiosity, as many writers do. Tingle carefully weaves the themes of tradition, pride in one's heritage, family, and identity in with his dominant theme of spirituality to allow the reader a complex view of the Native American experience. Two outstanding examples of this fact occur near the end of the story. The first example can be found on page 82: "Jimmy Ben thought he saw movement in the bush, but he couldnt' be sure. Then his grandfather drew in his breath and fired the dart, several feet to the left of the bush. At the same moment, a rabbit leapt from the bush. He caught the dart in his neck, twisted in mid-air, and fell to the ground. 'I didn't see the rabbit,' Jimmy said. 'I didn't either,' said his grandfather. 'That's the other part of what Miss Tubby told you. Go with your faith,'" (Tingle 82). The second example occurs in the final paragraph of the draft: "Even Tom Bigbee looked peaceful. He was lying dead at the base of the stump, a blowdart in his neck. White feathers clung to the skin around the wound. Jimmy Ben and his family continued working to the good. Neither Tom Bigbee nor any other witch owl ever bothered them again" (Tingle 83). Both passages speak to Tingle's use of specificity to address pan-Native American peoples, as well as his ability to create a satisfying and beautifully crafted narrative that deals with the crucial theme of Native American spirituality.

MODERN NATIVE AMERICAN SPIRITUALITY

Native American spirituality is a commonly discussed topic in literature and academia today, and it continues to hold the interest of the public. I found the documentary above to be a fascinating look into a variety of aspects of Native American spirituality.

I also found the article, "Spirituality" in PBS' Indian Country Diaries series to be enlightening and to provide wonderful insight into the Native American spiritual experience.